I was brought up in a small unionist home. We had all the usual trappings — not least half the family being from Ballymena. Every 12th of July we sat on the Lisburn Road to watch the parade. I went to mono-cultural schools. Sundays were for putting on the church outfit, going to church and Sunday school. Politics barely entered the house until 1968, when even at ten years old I could sense that the news was beginning to reshape our lives.

Then the Troubles began. Civil Rights marches appeared on the black-and-white TV, accompanied by a running family commentary that somehow placed the blame for RUC batons on the people being beaten. They “shouldn’t have been there,” I was told.

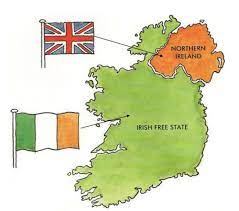

From that point on, everything was framed through a single fault line. If people wanted the Free State, they should go and live in it. The Army should “go up to the Falls and sort things out.” At school we had one Catholic in our entire year. I can’t repeat what was said after Bloody Sunday. Until I went to Queen’s in 1977 to study history and politics, I accepted the standard Protestant narrative: that our country was being ravaged by the IRA for no reason other than a desire for a united Ireland.

And we still hear that version today — that the Troubles were the IRA. Loyalist groups even build the word “Defence” into their titles, forgetting that the first major attacks in 1969 targeted Catholics in mixed estates.

Unionism had been given a chance. Partition in 1920 introduced proportional representation to ensure fairness. The first two Northern Ireland elections used PR. But by 1929 it was gone. After WWII, the UK abolished property-based voting in local elections; Unionists kept it because it served their interests. Ironically, it disenfranchised more working-class Protestants than Catholics — but it helped secure unionist control. Power depended on prosperity, property ownership, and patronage, so the system rewarded Unionists and penalised Catholics.

In Derry, a nationalist majority somehow produced a unionist council by twelve seats to eight — classic Gerry-mandering. In 1922 PR was removed from local elections entirely, and boundaries were redrawn to guarantee unionist dominance. Twelve nationalist councils became unionist overnight. Northern Ireland’s second university was moved from Derry to Coleraine largely to preserve that gerrymander — and because of pure sectarian instincts.

Second-class citizenship wasn’t hidden; it was accepted. Both communities knew it. Manufacturing and engineering jobs were overwhelmingly Protestant. In the public sector, overall employment numbers looked balanced, but seniority told the real story. In 1968, of 1,095 senior civil-service posts, only 130 were held by Catholics. In Derry, just 30% of administrative staff were Catholic; in Dungannon, none. In Fermanagh, no senior council post was ever held by a Catholic. From 1921 to 1968, only one Catholic became a Permanent Secretary. Down to staff-officer grade, fourteen out of 229 were Catholic. In 1969, just six of sixty-eight judicial appointments were Catholic.

There is much more evidence, if you want to read it.

Unionists owned all political power in Northern Ireland — elected offices, civil-service leadership, and the institutions that implemented policy. Those in authority were overwhelmingly from one community and acted in its interests. Add in day-to-day discrimination: Protestant employers hiring Protestants, often justified with lazy sectarian tropes like “Catholics don’t want to work.” I know how this works personally. At RBAI, old-boy networks created opportunities for Protestant children simply because their parents knew each other from school. It wasn’t always consciously discriminatory, but the effect certainly was.

Nationalist politicians were blocked at every turn. Equality simply did not exist. One-man-one-vote did not deliver democracy, and was never intended to — which is why Northern Ireland was originally designed to require PR. The UK government knew the state needed safeguards against discrimination. Unionists removed those safeguards, and London allowed a Protestant statelet to form. That is where responsibility lies.

The Civil Rights movement did not arise from ideology; it arose from necessity. Had Northern Ireland operated as intended — with equality as a founding principle — there would have been no need for marches. Had Stormont abolished property-based voting, fairness would at least have been possible. Had Paisley and the hard-liners not stamped out reform and intimidated the liberal Unionists who wanted to change things, we might be living in a very different place.

But Unionism did not want a fair system. It feared equality — and still does. So when you hear hard-right attacks on Sinn Féin or Dublin, remember where the roots of the problem actually lie.

This is not a justification for violence. It is a reality check. A history long ignored, for very deliberate political reasons.

all so very true & I just wish more Protestants, a minority of Catholics & the free state privelege would at least acknowledge the truth of the matter.

LikeLike